Digitizing the network

Data to develop new drugs

In the late 19th century, pathogen-immune serum was first used as a treatment against infectious disease. This lead to generations of work on antibiotics, resulting in sulfa drugs by 1936 and penicillin in 1943. Nearly all of the antibiotics in use today are compounds that were discovered during the 1940s to 1960s - the golden era of antibiotic discovery - or their derivatives.

A war now rages between man and microbe, as resistance threatens the effectiveness of these antibiotics and antivirals. Yet, new therapeutic strategies are increasingly based upon emerging molecular details of the infectious disease lifecycle. During my PhD, I worked on a data-rich strategy for uncovering the molecular lifecycle of human viral pathogens.

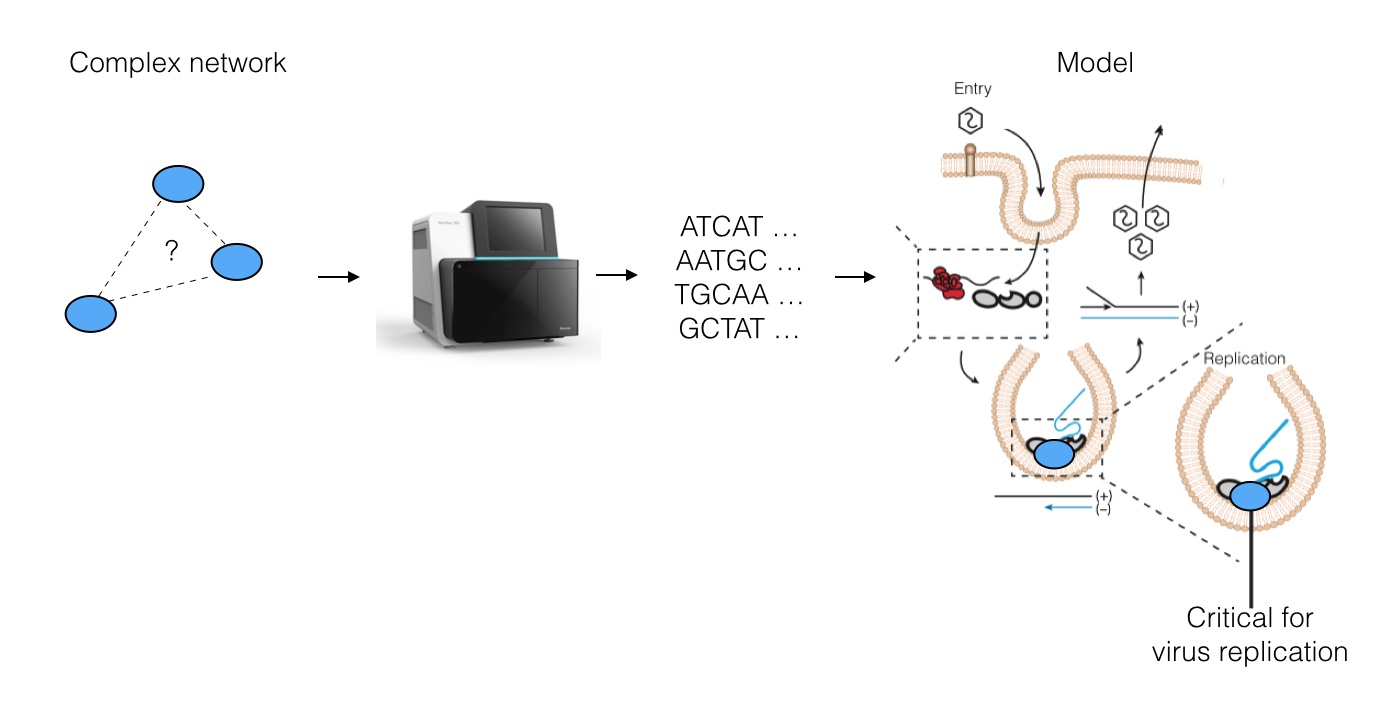

Specifically, we asked whether Next-Generation DNA Sequencing (NGS) can be used to understand viral replication mechanisms. We developed a way to digitize cellular networks using NGS, resulting in huge volumes of data about the specific interactions between human proteins and RNA viral genomes. We then use this data to re-construct a model for how the virus may replicate its genome.

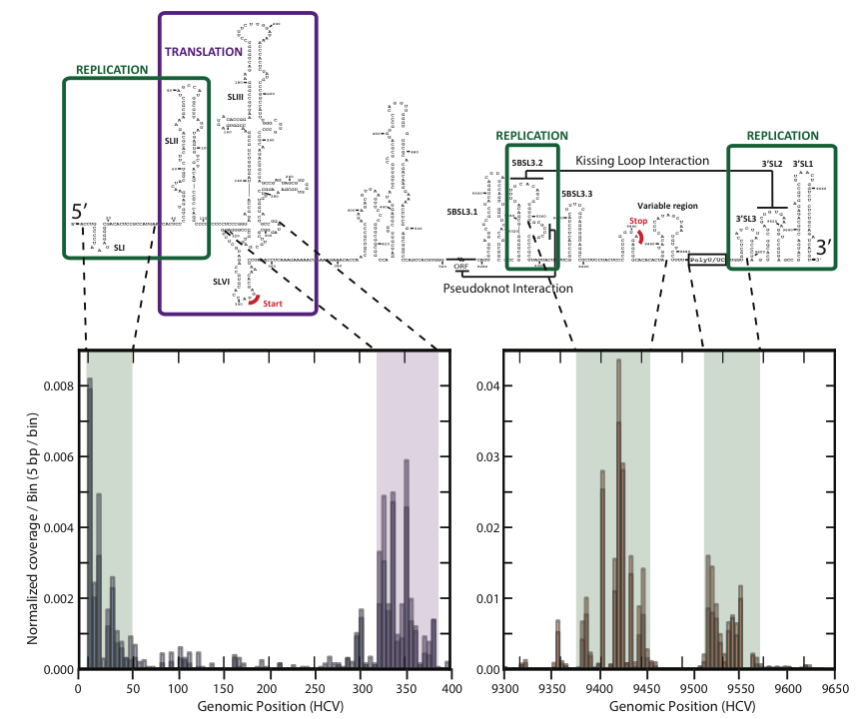

The strategy works as follows: we pick a protein required for the virus to live (many are known, but few are well-understood) and we use biochemical tricks along with NGS to read out an "imprint" of all regions on the viral genome that directly contact the protein inside live cells. This results in a coverage histogram of binding activity across the virus, which can be further analyzed.

NGS results a large file of (~30 million) strings corresponding to all fragments of RNA to which the protein bound in the virus-infected cells. To isolate fragments that come from the virus, we use string matching algorithms to remove all human-derived fragments. We built a pipeline in python do this, taking advantage of the Pandas library for data processing and analysis.

We wrapped all data filtering algorithms in python functions using subprocess calls (though libraries to build make-like workflows are also very useful here and we have used them for other projects). For example, the commonly used, ultrafast, and memory-efficient short-string aligner bowtie2 can pretty easily be called from within the python code easily:

program='bowtie2'

process=subprocess.Popen([program,'-x',index,'-k',k,'-U',infastq,'--un',unmapped,'-S',outfile],stderr=subprocess.STDOUT,stdout=subprocess.PIPE)

We used Pandas for SQL-like dataframe processing. Mainly, we used this to partition strings into various taxonomic bins based upon the type of gene (e.g., coding human RNA, non-coding human gene, viral genome), which are encoded using ensembl gene IDs. (Jeff Hammerbacher's lab at Mt. Sinai recently released PyEnsembl, which would have been very useful this!)

hmap_m=pd.merge(hmap,pc_genes,left_on='ENSG_ID',right_on='ENSG_ID',how='inner')

The pipeline puts the sequenced fragments into bins based upon RNA type and provides statistics and visualizations about the contents of each bin as well as iPython notebooks for interactive exploration (see docs here). It also provides a detailed footprint of binding activity for any protein across any viral RNA genome (shown below for Hepatitis-C virus and poly-C binding protein, PCBP).

Applying the pipeline

From the mapping of PCBP to Hepatitis-C, we uncovered new details about how the virus replicates (RNA, 2014). We also applied this tool to retroviruses and discovered that embryo development occurs in the presence of retroviral proteins (Nature, in press, 2015)! We used it to discover something fundamental about ribosomes (Nature, 2014) and to study brain cancers (in review).